Abstract

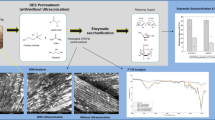

Tomato overproduce is utilized as raw material for lycopene extraction. This research employs a novel approach for lycopene separation: chitosan/polyvinylpyrrolidone (CS/PVP) pervaporation membranes. According to the application of this novel approach, PV acts as a concentration technique of lycopene. To prevent thermal degradation of lycopene, pervaporative separation of lycopene is explored and the results are presented. Lycopene/acetone feed solution is fed to pervaporation unit for efficient separation of lycopene using membranes that are fabricated by a blend of biopolymer and synthetic polymer, viz., chitosan (CS) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), respectively. CS and CS/PVP blend membranes are characterized using differential thermal analysis (TG-DTA), field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to study their thermal properties, structural morphology, and chemical composition, respectively. The pervaporative performance of the CS/PVP blend membranes is studied by evaluating total flux and selectivity. The process is optimized for maximum flux and selectivity using response surface methodology. The higher selectivity values indicate the possibility of using the pervaporative separation process on an industrial scale. The findings of this research show the efficient separation of lycopene using pervaporation membrane–based technology compared to conventional separation techniques. This is the first time that pervaporation process is being used for lycopene separation from solvent using novel CS/PVP membrane.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed Apr. 19, 2023).

Løvdal T, Van Droogenbroeck B, Eroglu EC et al (2019) Valorization of tomato surplus and waste fractions: a case study using Norway, Belgium, Poland, and Turkey as examples. Foods 8(7):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070229

Gatahi DM (2020) Challenges and opportunities in tomato production chain and sustainable standards. Int J Hortic Sci Technol 7(3):235–262. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijhst.2020.300818.361

Gulati A, Wardhan H, Sharma P (2022) Tomato, onion and potato (TOP) value chains. Agricultural value chains in India. Springer Nature, pp 33–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4268-2_3

‘Tomato prices hit rock bottom’. . Accessed: Feb. 13, 2023, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/chhattisgarh-farmers-tomato-low-prices-huge-losses-increased-production-reduced-demand-2309721-2022-12-15

Schieber A, Stintzing FC, Carle R (2001) By-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds — recent developments. Trends Food Sci Technol 12(11):401–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-2244(02)00012-2

Eggersdorfer M, Wyss A (2018) Carotenoids in human nutrition and health. Arch Biochem Biophys 652:18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2018.06.001

Trombino S, Cassano R, Procopio D, Di Gioia ML, Barone E (2021) Valorization of tomato waste as a source of carotenoids. Molecules 26(16):5062. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26165062

Saini RK, Moon SH, Keum Y-S (2018) An updated review on use of tomato pomace and crustacean processing waste to recover commercially vital carotenoids. Food Res Int 108:516–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.003

Anlar HG, Bacanli M (2020) Lycopene as an antioxidant in human health and diseases. In: Pathology: Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants. Elsevier, pp 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815972-9.00024-X

Rao AV, Rao LG (2007) Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol Res 55(3):207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.012

D. Agarwal and R. Are, ‘Review Synthèse’, 2000.

Sharifi-Rad M et al (2020) Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front Physiol 11:694. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00694

Kong KW, Khoo HE, Prasad KN, Ismail A, Tan CP, Rajab NF (2010) Revealing the power of the natural red pigment lycopene. Molecules 15(2):959–987. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15020959

Li N et al (2021) Tomato and lycopene and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review. Food Chem 343:128396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128396

Cooperstone JL et al (2017) Tomatoes protect against development of UV-induced keratinocyte carcinoma via metabolomic alterations. Sci Rep 7(1):5106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05568-7

Imran M et al (2020) Lycopene as a natural antioxidant used to prevent human health disorders. Antioxidants 9(8):706. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9080706

Sasidharan S, Chen Y, Saravanan D, Sundram KM, Yoga Latha L (2011) Extraction, isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from plants’ extracts. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 8(1):1–10

Chutia H, Mahanta CL (2021) Green ultrasound and microwave extraction of carotenoids from passion fruit peel using vegetable oils as a solvent: optimization, comparison, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 67:102547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102547

de Souza AL, Gomes FD, Tonon RV, da Silva LF, Cabral LM (2019) Coupling membrane processes to obtain a lycopene-rich extract. J Food Process Preserv 43(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.14164

Alsobh A, Zin MM, Vatai G, Bánvölgyi S (2022) The application of membrane technology in the concentration and purification of plant extracts: a review. Period Polytech Chem Eng 66(3):394–408. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPch.19487

Charcosset C (2016) Ultrafiltration, microfiltration, nanofiltration and reverse osmosis in integrated membrane processes. In: Integrated Membrane Systems and Processes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Oxford, UK, pp 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118739167.ch1

Castro-Muñoz R et al (2019) Towards the dehydration of ethanol using pervaporation cross-linked poly(vinyl alcohol)/graphene oxide membranes. J Membr Sci 582:423–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2019.03.076

Castro-Muñoz R (2020) Breakthroughs on tailoring pervaporation membranes for water desalination: a review. Water Res 187:116428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116428

Castro-Muñoz R, de la Iglesia Ó, Fíla V, Téllez C, Coronas J (2018) Pervaporation-assisted esterification reactions by means of mixed matrix membranes. Ind Eng Chem Res 57(47):15998–16011. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b01564

Castro-Muñoz R (2019) Pervaporation: the emerging technique for extracting aroma compounds from food systems. J Food Eng 253:27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.02.013

Castro-Muñoz R et al (2019) Graphene oxide – filled polyimide membranes in pervaporative separation of azeotropic methanol–MTBE mixtures. Sep Purif Technol 224:265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2019.05.034

Castro-Muñoz R, Ahmad MZ, Cassano A (2023) Pervaporation-aided processes for the selective separation of aromas, fragrances and essential (AFE) solutes from agro-food products and wastes. Food Rev Intl 39(3):1499–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2021.1934008

Msahel A et al (2021) Exploring the effect of iron metal-organic framework particles in polylactic acid membranes for the azeotropic separation of organic/organic mixtures by pervaporation. Membranes (Basel) 11(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11010065

Castro-Muñoz R (2023) A critical review on electrospun membranes containing 2D materials for seawater desalination. Desalination 555:116528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2023.116528

Yodjun P, Soontarapa K, Eamchotchawalit C (2011) Separation of lycopene/solvent mixture by chitosan membranes. J Met Mater Miner 21(1)

Nazir A, Khan K, Maan A, Zia R, Giorno L, Schroën K (2019) Membrane separation technology for the recovery of nutraceuticals from food industrial streams. Trends Food Sci Technol 86:426–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.02.049

Castro-Muñoz R, González-Valdez J, Ahmad MZ (2020) High-performance pervaporation chitosan-based membranes: new insights and perspectives. Rev Chem Eng 37(8):959–974. https://doi.org/10.1515/revce-2019-0051

Azmana M, Mahmood S, Hilles AR, Rahman A, Bin Arifin MA, Ahmed S (2021) A review on chitosan and chitosan-based bionanocomposites: promising material for combatting global issues and its applications. Int J Biol Macromol 185:832–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.023

Rosli NAH et al (2020) Review of chitosan-based polymers as proton exchange membranes and roles of chitosan-supported ionic liquids. Int J Mol Sci 21(2):632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21020632

Anjali Devi D, Smitha B, Sridhar S, Aminabhavi TM (2006) Novel crosslinked chitosan/poly(vinylpyrrolidone) blend membranes for dehydrating tetrahydrofuran by the pervaporation technique. J Membr Sci 280(1–2):45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2006.01.003

Novak U et al (2020) From waste/residual marine biomass to active biopolymer-based packaging film materials for food industry applications – a review. Phys Sci Rev 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2019-0099

Lavrič G, Oberlintner A, Filipova I, Novak U, Likozar B, Vrabič-Brodnjak U (2021) Functional nanocellulose, alginate and chitosan nanocomposites designed as active film packaging materials. Polymers (Basel) 13(15):2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13152523

Bajić M, Ročnik T, Oberlintner A, Scognamiglio F, Novak U, Likozar B (2019) Natural plant extracts as active components in chitosan-based films: a comparative study. Food Packag Shelf Life 21:100365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100365

Pataro G, Carullo D, Falcone M, Ferrari G (2020) Recovery of lycopene from industrially derived tomato processing by-products by pulsed electric fields-assisted extraction. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 63:102369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102369

Zhang QG, Hu WW, Zhu AM, Liu QL (2013) UV-crosslinked chitosan/polyvinylpyrrolidone blended membranes for pervaporation. RSC Adv 3(6):1855–1861. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ra21827e

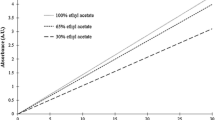

Zhang XH, Liu QL, Xiong Y, Zhu AM, Chen Y, Zhang QG (2009) Pervaporation dehydration of ethyl acetate/ethanol/water azeotrope using chitosan/poly (vinyl pyrrolidone) blend membranes. J Membr Sci 327(1–2):274–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2008.11.034

Cao S, Shi Y, Chen G (1999) Properties and pervaporation characteristics of chitosan-poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) blend membranes for MeOH-MTBE. J Appl Polym Sci 74(6):1452–1458. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19991107)74:6<1452::AID-APP18>3.0.CO;2-N

Zhang QG, Hu WW, Liu QL, Zhu AM (2013) Chitosan/polyvinylpyrrolidone-silica hybrid membranes for pervaporation separation of methanol/ethylene glycol azeotrope. J Appl Polym Sci 129(6):3178–3184. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.39058

Zhang QG, Han GL, Hu WW, Zhu AM, Liu QL (2013) Pervaporation of methanol–ethylene glycol mixture over organic–inorganic hybrid membranes. Ind Eng Chem Res 52(22):7541–7549. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie400290z

Pandya D (2017) ‘Standardization of solvent extraction process for lycopene extraction from tomato pomace. J Appl Biotechnol Bioeng 2(1). https://doi.org/10.15406/jabb.2017.02.00019

Mendelová A, Mendel Ľ, Fikselová M, Czako P (2013) Effect of drying temperature on lycopene content of processed tomatoes. Potr S J F Sci 7(1):141–145. https://doi.org/10.5219/300

Solak EK, Şanli O (2010) Use of sodium alginate-poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) membranes for pervaporation separation of acetone/water mixtures. Sep Sci Technol 45(10):1354–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496391003608256

Najafi M, Mousavi SM, Saljoughi E (2018) Preparation and characterization of poly(ether block amide)/graphene membrane for recovery of isopropanol from aqueous solution via pervaporation. Polym Compos 39(7):2259–2267. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.24203

Wang X-P, Shen Z-Q, Zhang F-Y, Zhang Y-F (1996) A novel composite chitosan membrane for the separation of alcohol-water mixtures. J Membr Sci 119(2):191–198

Mare R et al (2022) A rapid and cheap method for extracting and quantifying lycopene content in tomato sauces: effects of lycopene micellar delivery on human osteoblast-like cells. Nutrients 14(3):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030717

Irudayaraj J, Xu R, Tewari J (2003) Rapid determination of invert cane sugar adulteration in honey using FTIR spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. J Food Sci 68(6):2040–2045. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb07015.x

Vasconcelos AG et al (2021) Promising self-emulsifying drug delivery system loaded with lycopene from red guava (Psidium guajava L.): in vivo toxicity, biodistribution and cytotoxicity on DU-145 prostate cancer cells. Cancer Nanotechnol 12(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-021-00103-w

Raduly MF et al (2011) Lycopene determination in tomatoes by different spectral techniques (UV-VIS, FTIR and HPLC). Virtual Company of Physics

Kamil MM, Mohamed GF, Shaheen MS (2011) Fourier transformer infrared spectroscopy for quality assurance of tomato products. J Am Sci 7:559–572

Priam F, Marcelin O, Marcus R, Jô L-F, Smith-Ravin EJ (2017) Lycopene extraction from Psidium guajava L. and evaluation of its antioxidant properties using a modified DPPH test. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Technol 11(4):67–73. https://doi.org/10.9790/2402-1104016773

A. Dedić and A. Alispahic, ‘Extraction and chemical characterization of lycopene from fresh and processed tomato fruit’, 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328043676

Almwli HHA, Mousavi SM, Kiani S (2021) Preparation of poly(butylene succinate)/polyvinylpyrrolidone blend membrane for pervaporation dehydration of acetone. Chem Eng Res Des 165:361–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2020.10.033

Teodorescu M, Bercea M (2015) Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) – a versatile polymer for biomedical and beyond medical applications. Polym-Plast Technol Eng 54(9):923–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/03602559.2014.979506

Zereshki S et al (2010) Poly(lactic acid)/poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) blend membranes: effect of membrane composition on pervaporation separation of ethanol/cyclohexane mixture. J Membr Sci 362(1–2):105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2010.06.025

Zhu T, Luo Y, Lin Y, Li Q, Yu P, Zeng M (2010) Study of pervaporation for dehydration of caprolactam through blend NaAlg–poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) membranes on PAN supports. Sep Purif Technol 74(2):242–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2010.06.012

Cui L et al (2018) Preparation and characterization of chitosan membranes. RSC Adv 8(50):28433–28439. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8RA05526B

Güneş-Durak S, Ormancı-Acar T, Tüfekci N (2018) Effect of PVP content and polymer concentration on polyetherimide (PEI) and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) based ultrafiltration membrane fabrication and characterization. Water Sci Technol 2017(2):329–339. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2018.142

Nayab SS et al (2021) Anti-foulant ultrafiltration polymer composite membranes incorporated with composite activated carbon/chitosan and activated carbon/thiolated chitosan with enhanced hydrophilicity. Membranes (Basel) 11(11):827. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11110827

Samanta HS, Ray SK (2015) Pervaporative recovery of acetone from water using mixed matrix blend membranes. Sep Purif Technol 143:52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2015.01.015

Wilson R et al (2011) Influence of clay content and amount of organic modifiers on morphology and pervaporation performance of EVA/clay nanocomposites. Ind Eng Chem Res 50(7):3986–3993. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie102259s

Machado DR, Hasson D, Semiat R (1999) Effect of solvent properties on permeate flow through nanofiltration membranes. Part I: Investigation of parameters affecting solvent flux. J Membr Sci 163(1):93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-7388(99)00158-1

Funding

The authors wish to thank the Department of Science & Technology, Science for Equity Empowerment and Development (DST - SEED) Division, Government of India, for grant support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kanchan A. Nandeshwar studied and worked over the extraction mechanism of lycopene and fabrication processes of CS/PVP membrane and performed the experiments for the pervaporation process. Dr. S. M. Kodape studied and suggested over different methodologies involved in the preparation of pervaporation membranes. Ajit P. Rathod studied whether the concentration variation affects the morphology of the finished product. Dr. Sangesh P. Zodape investigated the requisite analytical techniques for confirming successful outcomes. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Solvent extraction of lycopene from tomato waste followed by pervaporation.

• Fabrication of pervaporative membranes using a blend of polymers—chitosan and polyvinylpyrrolidone and utilization of fabricated membrane for pervaporative separation of lycopene in crystal form and simultaneous recovery of solvent.

• Study of operating parameters for pervaporative separation of lycopene using pure and blend membranes—effect of membrane thickness, feed concentration, and feed temperature.

• Optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology and ANOVA.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nandeshwar, K.A., Kodape, S.M., Rathod, A.P. et al. Coupling solvent extraction with pervaporation for efficient separation of lycopene from tomato waste using chitosan/polyvinylpyrrolidone (CS/PVP) pervaporative membranes and its optimization study. Biomass Conv. Bioref. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04879-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04879-2